Is Surgery Necessary for a Knee Dislocation? CORE Omaha Explains…

CORE Physical Therapy In Omaha Explains…

CORE Physical Therapy In Omaha Explains…

By Dr. Mark Rathjen PT DPT CSCS

CORE Physical Therapy Co-owner

17660 Wright Street Suites 9/10

Omaha, NE 68130

Surgery is often the end result of a patient that experiences chronic knee dislocations, but is that the best answer? The classic answer of “it depends” applies here. The below study confirms this, as both indications show similar outcomes, though surgical is better. Though surgical outcomes are performed on chronic dislocations much more often that just an acute first time consequence.

Clinically, the surgery is very successful if a full rehab and strict return to activity is performed and adhered to. I have also found this is more for the population who has experience more than 2-3 subluxations in less than 1-2 years. First time subluxation have good efficacy of being rehabbed without issue.

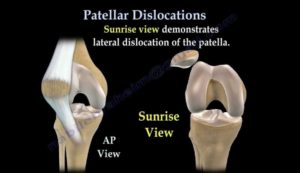

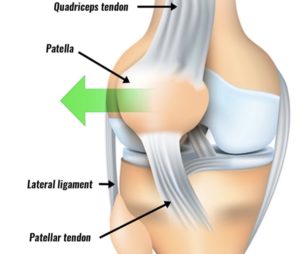

Rehab without surgery involves hip strengthening, mobility and symmetry, mechanical proprioception, and joint mobility. Overall, more than 75% of the one time only subluxation group that we see clinically do not need surgery in 1-2 years. Those that have dislocated more than once often have a bigger issue with laxity, would be more likely to benefit from the surgical intervention. Nearly all dislocations of the knee cap happen laterally, and the issues with lack of balance and laxity must be addressed when possible.

Either way, knee dislocation is not a death sentence to an athlete. We see these patients with and without surgery to the tune of 20-30 per year, as its not uncommon. Nearly all go back to their respective sports at full capacity. That’s what we do here at CORE Physical Therapy In Omaha. We get our athletes and patients better than before.

THIS IS WHO WE ARE, THIS IS WHAT WE DO.

C.O.R.E. Physical Therapy and Sports Performance PC,

17660 Wright St, Suites 9/10

Omaha, NE 68130

402-930-4027

At CORE Physical Therapy in Omaha, We specialize in the treatment of athletes. We have worked with athletes for a combined 30 years.

This is who are, This is what we do.

Owned and Operated

by

Dr. Mark Rathjen and Dr. Claire Rathjen.

CORE is a family owned business

est. 2015

We are proud to serve the greater Omaha metro area.

For More information, Please feel free to contact us https://coreomaha.com/contact/

Please feel free to follow us at https://www.facebook.com/COREomaha/

To get started https://coreomaha.com/getting-started/

For more Blog information https://coreomaha.com/blog/

Youtube Account linked below.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCVg8OSN5h-i1n_ykw1Gvahg?view_as=subscriber

. 2015 Feb 26;(2):CD008106.

doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008106.pub3.

Surgical versus non-surgical interventions for treating patellar dislocation

- PMID: 25716704

- DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008106.pub3

Free article

Abstract

Background: Patellar dislocation occurs when the patella disengages completely from the trochlear (femoral) groove. Following reduction of the dislocation, conservative (non-surgical) rehabilitation with physiotherapy may be used. Since recurrence of dislocation is common, some surgeons have advocated surgical intervention rather than non-surgical interventions. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2011.

Objectives: To assess the effects (benefits and harms) of surgical versus non-surgical interventions for treating people with primary or recurrent patellar dislocation.

Search methods: We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group’s Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, EMBASE, AMED, CINAHL, ZETOC, Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and a variety of other literature databases and trial registries. Corresponding authors were contacted to identify additional studies. The last search was carried out in October 2014.

Selection criteria: We included randomised and quasi-randomised controlled clinical trials evaluating surgical versus non-surgical interventions for treating lateral patellar dislocation.

Data collection and analysis: Two review authors independently examined titles and abstracts of each identified study to assess study eligibility, extract data and assess risk of bias. The primary outcomes we assessed were the frequency of recurrent dislocation, and validated patient-rated knee or physical function scores. We calculated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences MD) for continuous outcomes. When appropriate, we pooled data.

Main results: We included five randomised studies and one quasi-randomised study. These recruited a total of 344 people with primary (first-time) patellar dislocation. The mean ages in the individual studies ranged from 19.3 to 25.7 years, with four studies including children, mainly adolescents, as well as adults. Follow-up for the full study populations ranged from two to nine years across the six studies. The quality of the evidence is very low as assessed by GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group) criteria, with all studies being at high risk of performance and detection biases, relating to the lack of blinding.There was very low quality but consistent evidence that participants managed surgically had a significantly lower risk of recurrent dislocation following primary patellar dislocation at two to five years follow-up (21/162 versus 32/136; RR 0.53 favouring surgery, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.33 to 0.87; five studies, 294 participants). Based on an illustrative risk of recurrent dislocation in 222 people per 1000 in the non-surgical group, these data equate to 104 fewer (95% CI 149 fewer to 28 fewer) people per 1000 having recurrent dislocation after surgery. Similarly, there is evidence of a lower risk of recurrent dislocation after surgery at six to nine years (RR 0.67 favouring surgery, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.08; two studies, 165 participants), but a small increase cannot be ruled out. Based on an illustrative risk of recurrent dislocation in 336 people per 1000 in the non-surgical group, these data equate to 110 fewer (95% CI 195 fewer to 27 more) people per 1000 having recurrent dislocation after surgery.The very low quality evidence available from single trials only for four validated patient-rated knee and physical function scores (the Tegner activity scale, KOOS, Lysholm and Hughston VAS (visual analogue scale) score) did not show significant differences between the two treatment groups.The results for the Kujala patellofemoral disorders score (0 to 100: best outcome) differed in direction of effect at two to five years follow-up, which favoured the surgery group (MD 13.93 points higher, 95% CI 5.33 points higher to 22.53 points higher; four studies, 171 participants) and the six to nine years follow-up, which favoured the non-surgical treatment group (MD 3.25 points lower, 95% CI 10.61 points lower to 4.11 points higher; two studies, 167 participants). However, only the two to five years follow-up included the clear possibility of a clinically important effect (putative minimal clinically important difference for this outcome is 10 points).Adverse effects of treatment were reported in one trial only; all four major complications were attributed to the surgical treatment group. Slightly more people in the surgery group had subsequent surgery six to nine years after their primary dislocation (20/87 versus 16/78; RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.89, two studies, 165 participants). Based on an illustrative risk of subsequent surgery in 186 people per 1000 in the non-surgical group, these data equate to 11 more (95% CI 76 fewer to 171 more) people per 1000 having subsequent surgery after primary surgery.

Authors’ conclusions: Although there is some evidence to support surgical over non-surgical management of primary patellar dislocation in the short term, the quality of this evidence is very low because of the high risk of bias and the imprecision in the effect estimates. We are therefore very uncertain about the estimate of effect. No trials examined people with recurrent patellar dislocation. Adequately powered, multi-centre, randomised controlled trials, conducted and reported to contemporary standards, are needed. To inform the design and conduct of these trials, expert consensus should be achieved on the minimal description of both surgical and non-surgical interventions, and the anatomical or pathological variations that may be relevant to both choice of these interventions and the natural history of patellar instability. Furthermore, well-designed studies recording adverse events and long-term outcomes are needed.