CORE Physical Therapy In Omaha Explains…

By Dr. Mark Rathjen PT DPT CSCS

CORE Physical Therapy Co-owner

17660 Wright Street Suites 9/10

Omaha, NE 68130

The study below is interesting overall as it does point to some quality evidence for treatment of PF syndrome, especially adding in hip exercises. From other studies we also know this be true. We do know, however, strengthening is only part of the equation. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25603546/

Balance, mechanical training, proprioceptive training, and symmetrical range and Rom mobility work are also imperative to the treatment of the condition. Furthermore, we need to figure out the root cause of the condition itself. Is this an overuse syndrome, a mechanical issue? Is there some type of movement disorder that or asymmetric on the symptom or non symptom side cause over use?

All of the above can be contributing factors and need proper assessment by a trained doctor of physical therapy. A physical therapist who treats sports and active patients primarily in a specialty is infinitely better than a generalist. Would you want your family medicine doctor doing your orthopedic surgery? Not likely. Same example here. Seek out a specialist and you will see better, faster and more permanent results from your condition.

CORE Physical Therapy in Omaha specializes in athletes and has a full sports facility to assess any of your concerns. We also have a full gym, and conditioning turf with slow motion analysis capability to allow for proper diagnosis of any mechanical compensations and deficiencies .

C.O.R.E. Physical Therapy and Sports Performance PC,

17660 Wright St, Suites 9/10

Omaha, NE 68130

402-930-4027

At CORE Physical Therapy in Omaha, We specialize in the treatment of athletes. We have worked with athletes for a combined 30 years.

This is who are, This is what we do.

Owned and Operated

by

Dr. Mark Rathjen and Dr. Claire Rathjen.

CORE is a family owned business

est. 2015

We are proud to serve the greater Omaha metro area.

For More information, Please feel free to contact us https://coreomaha.com/contact/

Please feel free to follow us at https://www.facebook.com/COREomaha/

To get started https://coreomaha.com/getting-started/

For more Blog information https://coreomaha.com/blog/

Exercise for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome

- PMID: 25603546

- DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010387.pub2

Abstract

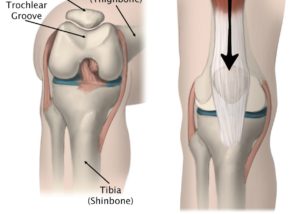

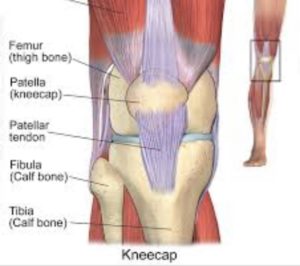

Background: Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is a common knee problem, which particularly affects adolescents and young adults. PFPS, which is characterised by retropatellar (behind the kneecap) or peripatellar (around the kneecap) pain, is often referred to as anterior knee pain. The pain mostly occurs when load is put on the knee extensor mechanism when climbing stairs, squatting, running, cycling or sitting with flexed knees. Exercise therapy is often prescribed for this condition.

Objectives: To assess the effects (benefits and harms) of exercise therapy aimed at reducing knee pain and improving knee function for people with patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Search methods: We searched the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialised Register (May 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2014, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1946 to May 2014), EMBASE (1980 to 2014 Week 20), PEDro (to June 2014), CINAHL (1982 to May 2014) and AMED (1985 to May 2014), trial registers (to June 2014) and conference abstracts.

Selection criteria: Randomised and quasi-randomised trials evaluating the effect of exercise therapy on pain, function and recovery in adolescents and adults with patellofemoral pain syndrome. We included comparisons of exercise therapy versus control (e.g. no treatment) or versus another non-surgical therapy; or of different exercises or exercise programmes.

Data collection and analysis: Two review authors independently selected trials based on pre-defined inclusion criteria, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. Where appropriate, we pooled data using either fixed-effect or random-effects methods. We selected the following seven outcomes for summarising the available evidence: pain during activity (short-term: ≤ 3 months); usual pain (short-term); pain during activity (long-term: > 3 months); usual pain (long-term); functional ability (short-term); functional ability (long-term); and recovery (long-term).

Main results: In total, 31 heterogeneous trials including 1690 participants with patellofemoral pain are included in this review. There was considerable between-study variation in patient characteristics (e.g. activity level) and diagnostic criteria for study inclusion (e.g. minimum duration of symptoms) and exercise therapy. Eight trials, six of which were quasi-randomised, were at high risk of selection bias. We assessed most trials as being at high risk of performance bias and detection bias, which resulted from lack of blinding.The included studies, some of which contributed to more than one comparison, provided evidence for the following comparisons: exercise therapy versus control (10 trials); exercise therapy versus other conservative interventions (e.g. taping; eight trials evaluating different interventions); and different exercises or exercise programmes. The latter group comprised: supervised versus home exercises (two trials); closed kinetic chain (KC) versus open KC exercises (four trials); variants of closed KC exercises (two trials making different comparisons); other comparisons of other types of KC or miscellaneous exercises (five trials evaluating different interventions); hip and knee versus knee exercises (seven trials); hip versus knee exercises (two studies); and high- versus low-intensity exercises (one study). There were no trials testing exercise medium (land versus water) or duration of exercises. Where available, the evidence for each of seven main outcomes for all comparisons was of very low quality, generally due to serious flaws in design and small numbers of participants. This means that we are very unsure about the estimates. The evidence for the two largest comparisons is summarised here. Exercise versus control. Pooled data from five studies (375 participants) for pain during activity (short-term) favoured exercise therapy: mean difference (MD) -1.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) -2.39 to -0.54. The CI included the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 1.3 (scale 0 to 10), indicating the possibility of a clinically important reduction in pain. The same finding applied for usual pain (short-term; two studies, 41 participants), pain during activity (long-term; two studies, 180 participants) and usual pain (long-term; one study, 94 participants). Pooled data from seven studies (483 participants) for functional ability (short-term) also favoured exercise therapy; standardised mean difference (SMD) 1.10, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.63. Re-expressed in terms of the Anterior Knee Pain Score (AKPS; 0 to 100), this result (estimated MD 12.21 higher, 95% CI 6.44 to 18.09 higher) included the MCID of 10.0, indicating the possibility of a clinically important improvement in function. The same finding applied for functional ability (long-term; three studies, 274 participants). Pooled data (two studies, 166 participants) indicated that, based on the ‘recovery’ of 250 per 1000 in the control group, 88 more (95% CI 2 fewer to 210 more) participants per 1000 recovered in the long term (12 months) as a result of exercise therapy. Hip plus knee versus knee exercises. Pooled data from three studies (104 participants) for pain during activity (short-term) favoured hip and knee exercise: MD -2.20, 95% CI -3.80 to -0.60; the CI included a clinically important effect. The same applied for usual pain (short-term; two studies, 46 participants). One study (49 participants) found a clinically important reduction in pain during activity (long-term) for hip and knee exercise. Although tending to favour hip and knee exercises, the evidence for functional ability (short-term; four studies, 174 participants; and long-term; two studies, 78 participants) and recovery (one study, 29 participants) did not show that either approach was superior.

Authors’ conclusions: This review has found very low quality but consistent evidence that exercise therapy for PFPS may result in clinically important reduction in pain and improvement in functional ability, as well as enhancing long-term recovery. However, there is insufficient evidence to determine the best form of exercise therapy and it is unknown whether this result would apply to all people with PFPS. There is some very low quality evidence that hip plus knee exercises may be more effective in reducing pain than knee exercise alone.Further randomised trials are warranted but in order to optimise research effort and engender the large multicentre randomised trials that are required to inform practice, these should be preceded by research that aims to identify priority questions and attain agreement and, where practical, standardisation regarding diagnostic criteria and measurement of outcome.