https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2017.7285

CORE Physical Therapy In Omaha Explains…

By Dr. Mark Rathjen PT DPT CSCS

CORE Physical Therapy Co-owner

17660 Wright St. 9/10

Omaha NE

402-933-4027

“Limb symmetry indexes fre- quently overestimate knee function after ACLR and may be related to second ACL injury risk. These findings raise concern about whether the variable ACL return-to-sport criteria utilized in current clini- cal practice are stringent enough to achieve safe and successful return to sport.”

What does this mean?

It means the limb symmetry index is not unimportant, but it is not a full indicator of return to sports criteria. In Fact can give a false sense of recovery when there are other simulation, proprioceptive and sports specific drills that can tell a lot more about deficits and return to activities and sports alone.

Should we use the LSI?

Yes, its a quick and easy way to assess L vs R symmetry of power and strength. It does have limitations, but its not without value.

If I have 95% LSI should I got back to sports?

It depends. There are many factors that will lend better to determine that time frame. LSI is one factor, other testing and drills will be necessary to determine.

CORE Physical Therapy specializes in returning to sports at a better than before level after injuries or surgeries. We are based out of Omaha Nebraska and have served the Omaha area for nearly a decade.We use a unique and multi faceted approach to achieve the best results and are unique to every sport, position, and athlete.

COME see the CORE difference.

This is who we are, this is what we do

-Mark and Claire Rathjen PT DPT CSCS

At CORE Physical Therapy in Omaha, We specialize in the treatment of athletes. We have worked with athletes for a combined 30 years. CORE was established in 2015 by Dr. Mark and Dr. Claire Rathjen is family owned and operated.

Proud winners of the Omaha Choice awards for 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020,2021

We are proud to serve the greater Omaha metro area.

For More information, Please feel free to contact us http://coreomaha.com/contact/

Please feel free to follow us at https://www.facebook.com/COREomaha/

To get started http://coreomaha.com/getting-started/

For more Blog information http://coreomaha.com/blog/

Youtube Account linked below.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCVg8OSN5h-i1n_ykw1Gvahg?view_as=subscriber

Limb Symmetry Indexes Can Overestimate Knee Function After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

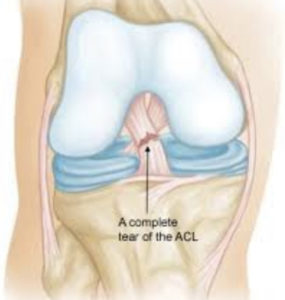

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury frequently results in muscle weakness, poor knee function, and increased risk for second injury, despite surgical anterior cruciate ligament

2,8,15,17-20

reconstruction (ACLR). Overall second ACL injury rates

reaching upward of 49%3 suggest inadequacy in current criteria used to

andprotectagainstsecondACLinjuryis needed.

Objective return-to-sport criteria often utilize measures of quadriceps strength and single-leg hop tests, with limb-to-limb differences typically ex- pressed as limb symmetry indexes (LSIs).3 Limb symmetry indexes use concurrent measures of the uninvolved limb as a ref- erence standard. While the uninvolved limb is widely used as a healthy control, bilateral muscle strength deficits have been demonstrated after ACL injury,11,16,20 challenging the validity of symmetry mea- sures in objective return-to-sport criteria. It is unknown whether measurements of the uninvolved limb prior to ACLR pro- vide a better reference than LSIs during return-to-sport testing. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the uninvolved limb as a reference standard for symmetry indexes utilized in return- to-sport testing and its relationship with second ACL injury rates. Preliminary evidence is presented to demonstrate po- tential benefits of using uninvolved-limb function prior to, instead of after, ACLR to determine return-to-sport readiness. We hypothesized that the involved-limb function of athletes after ACLR would more frequently match uninvolved-limb function measured concurrently after ACLR compared to uninvolved-limb function measured before ACLR, and

determine an athlete’s readiness to return to sport. Adherence to objective return- to-sport criteria reduces reinjury risk,8 but criteria used to clear patients for re-

turn to sport are not standardized and vary considerably.3 Evidence to establish optimal objective levels of knee func- tion that maximize functional outcomes

tUSTUDY DESIGN: Prospective cohort.

tUBACKGROUND: The high risk of second ante- rior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries after return to sport highlights the importance of return-to-sport decision making. Objective return-to-sport criteria frequently use limb symmetry indexes (LSIs) to quantify quadriceps strength and hop scores. Whether using the uninvolved limb in LSIs is optimal is unknown.

tUOBJECTIVES: To evaluate the uninvolved limb as a reference standard for LSIs utilized in return- to-sport testing and its relationship with second ACL injury rates.

tUMETHODS: Seventy athletes completed quad- riceps strength and 4 single-leg hop tests before anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) and 6 months after ACLR. Limb symmetry indexes for each test compared involved-limb measures

at 6 months to uninvolved-limb measures at 6 months. Estimated preinjury capacity (EPIC) levels for each test compared involved-limb measures

at 6 months to uninvolved-limb measures before ACLR. Second ACL injuries were tracked for a minimum follow-up of 2 years after ACLR.

tURESULTS: Forty (57.1%) patients achieved 90% LSIs for quadriceps strength and all hop tests. Only 20 (28.6%) patients met 90% EPIC levels (comparing the involved limb at 6 months after ACLR to the uninvolved limb before ACLR) for quadriceps strength and all hop tests. Twenty-four (34.3%) patients who achieved 90% LSIs for all measures 6 months after ACLR did not achieve 90% EPIC levels for all measures. Estimated preinjury capacity levels were more sensitive than LSIs in predicting second ACL injuries (LSIs, 0.273; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.010, 0.566 and EPIC, 0.818; 95% CI: 0.523, 0.949).

tUCONCLUSION: Limb symmetry indexes fre- quently overestimate knee function after ACLR and may be related to second ACL injury risk. These findings raise concern about whether the variable ACL return-to-sport criteria utilized in current clini- cal practice are stringent enough to achieve safe and successful return to sport.

tULEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Prognosis, 2b. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017;47(5):334-338. Epub 29 Mar 2017. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.7285

tUKEY WORDS: ACL, anterior cruciate ligament, rehabilitation, return to sport, symmetry

1Biomechanics and Movement Science Program, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. 2Division of Physical Therapy Education, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE. 3Department of Rehabilitation and Movement Sciences, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT. 4Department of Physical Therapy, University of Delaware, Newark, DE. This study was approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board. Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health (R37 HD037986, R01 AR048212, P30 GM103333). The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or financial involvement in any organization or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the article. Address correspondence to Dr Elizabeth Wellsandt, Division of Physical Therapy Education, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 984420 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4420. E-mail: elizabeth.wellsandt@unmc.edu t Copyright ©2017 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

334 | may 2017 | volume 47 | number 5 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on August 6, 2021. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2017 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

that estimated preinjury capacity (EPIC) levels would better predict second ACL injuries than LSIs.

METHODS

Athletes 14 to 55 years of age who were active in cutting and piv-

4

oting activities before complete

unilateral ACL injury were secondarily analyzed within a completed random- ized controlled trial and an ongoing pro- spective clinical trial.6,9 Exclusion criteria included a repairable meniscus, symp- tomatic grade III injury to other knee ligaments, greater than 1-cm2 full-thick- ness articular cartilage lesion, or prior ACL injury. This study was approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Patients completed 2 testing ses- sions before ACLR (testing 1, quadriceps strength testing initially after ACL injury; and testing 2, single-leg hop testing fol- lowing initial impairment resolution af- ter ACL injury) and 1 testing session after ACLR (testing 3, quadriceps strength testing and single-leg hop testing 6 months after ACLR) (FIGURE). Quadriceps strength was tested bilaterally in 90° of knee flexion by recording maximal vol- untary isometric contractions using the burst superimposition technique to en- sure normal quadriceps activation12 dur- ing the initial physical therapy evaluation acutely after ACL injury. Patients contin- ued rehabilitation prior to ACLR until initial impairments were resolved (effu- sion, range of motion, pain, gait impair- ments, quadriceps strength)12 and hop testing could be safely completed (sec- ond testing session). Four single-leg hop tests (single, crossover, and triple hop for distance; 6-meter timed hop) were com- pleted on each limb (uninvolved first).15 After 2 practice trials, the average of 2 trials was recorded in each limb for each hop test.

Patients underwent progressive, cri- terion-based postoperative rehabilita- tion early after ACLR1 and then repeated

quadriceps strength and single-leg hop testing 6 months after ACLR (testing 3), with LSIs calculated (see FIGURE). Six- month testing was chosen because it is a common time to begin sporting activi- ties.3 Symmetry was defined using a cut- off of 90% in accordance with established University of Delaware return-to-sport criteria that require 90% or greater LSIs in quadriceps strength and all 4 single- leg hop tests within a larger test battery.1 Return-to-sport criteria for included subjects also required at least 90% on the Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale and on a global rating score of knee function prior to physician clearance for returning to sport.1 An LSI of 85% to 90% or greater is common in other published return-to-sport crite- ria18,19 and thought to account for normal levels of interlimb asymmetry.13,21

In addition to computing LSIs 6 months after ACLR, EPIC levels were cal- culated by comparing the involved-limb

function at 6 months to uninvolved-limb scores prior to ACLR (FIGURE). A 90% cut- off was operationally defined as achieving EPIC levels for quadriceps strength and hop scores.

At subsequent follow-up testing, patients reported whether they had in- curred second ACL injuries during a minimum 2-year follow-up. All second injuries were confirmed by a licensed physician or physical therapist.

Statistical analyses were completed using PASW Version 23.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Correlational analyses were used to test whether time from ACL injury to initial uninvolved- limb testing (before ACLR) influenced EPIC levels. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the abil- ity of LSIs and EPIC levels to determine second ACL injury risk.10 Statistical sig- nificance was set at α≤.05.

|

Physical therapist initial evaluation ACL injury Impairment resolution Testing 2: uninvolved-limb hop tests ACLR 6 mo after ACLR Testing 3: involved- and uninvolved- limb quadriceps strength and hop tests

Testing 1: uninvolved-limb quadriceps strength Quadriceps strength LSI Involved Limb (6 mo) × 100 Uninvolved Limb (6 mo) Single, crossover, and triple hop LSI Involved (6 mo) × 100 Uninvolved (6 mo) 6-meter timed hop LSI Uninvolved Limb (6 mo) × 100 Involved Limb (6 mo) Quadriceps strength EPIC Involved Limb (6 mo) × 100 Uninvolved Limb (initial evaluation) Single, crossover, and triple hop EPIC Involved Limb (6 mo) × 100 Uninvolved Limb (impairment resolution) 6-meter timed hop EPIC Uninvolved Limb (impairment resolution) × 100 Involved Limb (6 mo)

|

||||

|

FIGURE. Timeline for testing and rehabilitation after ACL injury and equations used for calculation of LSIs and EPIC levels. Abbreviations: ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; EPIC, estimated preinjury capacity; LSI, limb symmetry index. |

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 47 | number 5 | may 2017 | 335

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on August 6, 2021. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2017 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

[ brief report ]

RESULTS

The initial cohort eligible for this study included 182 patients. Thirty-seven subjects completed nonoperative management of ACL in- jury, 9 did not complete hop testing prior to ACLR, 6 did not complete hop testing 6 months after ACLR, 28 did not return for testing 6 months after ACLR, and 32 were excluded to avoid unreliable EPIC measurements due to the use of different electromechanical dynamometers for quadriceps strength testing at each test- ing session. Thus, 70 patients (mean ± SD age, 26.6 ± 10.0 years; 32.9% women; body mass index, 24.9 ± 3.8 kg/m2) were used in the current analysis.

Patients completed the initial unin- volved-limb quadriceps strength testing at a mean ± SD of 1.5 ± 2.0 months and single-leg hop tests at 1.9 ± 2.1 months after ACL injury. Anterior cruciate liga- ment reconstruction occurred at a mean ± SD of 4.4 ± 4.0 months after injury (28 hamstring gracilis autografts, 42 soft tis- sue allografts). The time from ACL injury to initial uninvolved-limb testing did not impact strength or hop EPIC levels (P = .400-.892, Pearson r = –0.108 to 0.037).

Forty (57.1%) patients achieved 90% LSIs for quadriceps strength and all sin- gle-leg hop tests. Only 20 (28.6%) patients met 90% EPIC levels (comparing the in- volved limb at 6 months after ACLR to the uninvolved limb before ACLR) for quad- riceps strength and all hop tests. Twenty- four (34.3%) patients who achieved 90% LSIs for all measures 6 months after ACLR did not achieve 90% EPIC levels for all measures. TABLE 1 provides details for why 90% LSIs and EPIC levels were not achieved. When LSIs and EPIC lev- els were not achieved, mean quadriceps strength and hop scores ranged from 5.1% to 14.6% below 90% cutoff values (TABLE 2).

Eleven patients sustained a second ACL injury (ACLR to second injury time: median, 78 weeks; range, 27-276 weeks) (TABLE 3). Eight (4 ipsilateral, 4 contralat- eral) of the 11 patients with a second ACL injury passed 90% LSI return-to-sport cri-

teria in quadriceps strength and single-leg hop tests 6 months after initial ACLR, but 6 (4 ipsilateral, 2 contralateral) of these 8 did not achieve 90% EPIC levels in these measures. The use of 90% EPIC levels was superior to 90% LSIs in predicting second ACL injuries (LSIs: sensitivity, 0.273; 95% CI: 0.010, 0.566; specificity, 0.542; 95% CI: 0.417, 0.663; positive LR = 0.596; 95% CI: 0.218, 1.627; negative LR = 1.341; 95% CI: 0.871, 2.064 and EPIC: sensitivity, 0.818; 95% CI: 0.523, 0.949; specificity, 0.305; 95% CI: 0.203, 0.432; positive LR = 1.177; 95% CI: 0.850, 1.631; negative LR = 0.596; 95% CI: 0.161, 2.212).

DISCUSSION

T

es utilized in return-to-sport testing and its relationship with second ACL injury rates. The results of this study demon- strate that achievement of limb symmetry

in quadriceps strength and single-leg hop tests after ACLR does not guarantee that prior functional levels (per the uninvolved limb before ACLR) have been met. Of 70 patients, 40 met University of Delaware return-to-sport criteria of at least 90% symmetry in quadriceps strength and 4 single-leg hop tests 6 months after ACLR, but only 16 of these 40 patients achieved 90% EPIC levels when comparing the in- volved limb at 6 months to uninvolved- limb function prior to ACLR. Preliminary data suggest that the use of 90% EPIC levels is superior to 90% LSIs in predict- ing second ACL injuries.

The lower number of patients who met 90% EPIC levels compared to 90% LSIs may be explained by current criterion- based preoperative and postoperative rehabilitation that focuses on unilateral strengthening and neuromuscular train- ing.1 The uninvolved limb likely experienc- es limited physical activity beyond walking and activities of daily living during the ex- tended period between injury and return

TABLE 1

Patients Who Did Not Meet 90% LSI and 90% EPIC Levels by Specific Tests Not Passed

Measure/Specific Test n

Did not meet 90% LSIs Quadriceps strength Quadriceps strength Quadriceps strength Quadriceps strength Quadriceps strength 1hop

30 9

plus 1 hop 4 plus 2 hops 1 plus 3 hops 1 plus 4 hops 1

4

2hops

3hops 1 4hops 4

Did not meet 90% EPIC levels 50 Quadriceps strength 12 Quadriceps strength plus 1 hop 4 Quadriceps strength plus 2 hops 7 Quadriceps strength plus 3 hops 0 Quadriceps strength plus 4 hops 3 1hop 14 2hops 8 3hops 2 4hops 0

5

Abbreviations: EPIC, estimated preinjury capacity; LSI, limb symmetry index.

he purpose of this study was to

evaluate the uninvolved limb as a ref-

erence standard for symmetry index-

336 | may 2017 | volume 47 | number 5 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on August 6, 2021. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2017 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

TABLE 2

Quadriceps Strength and Single-Leg Hop Asymmetry Values When LSIs or EPIC Levels Were Less Than 90% for Each Measure

Reason for Not Meeting 90% LSIs n

Quadriceps strength 16 Single hop 18 Crossover hop 12 Triple hop 8 6-meter timed hop 9

Mean±SD,%

83.6 ± 3.2 81.1 ± 6.2 83.6 ± 4.3 84.9 ± 3.3 83.5 ± 4.5

Reason for Not Meeting 90% EPIC Levels

Quadriceps strength Single hop Crossover hop Triple hop

6-meter timed hop

n Mean ± SD, % 26 78.8 ± 8.3 18 75.4 ± 17.6 18 83.3 ± 5.4 12 81.7 ± 5.9 18 80.8 ± 6.5

Abbreviations: EPIC, estimated preinjury capacity; LSI, limb symmetry index.

TABLE 3

Patients With Second ACL Injuries and LSIs and EPIC Values

ACLR to Second

Patient ACL Injury, wk LSIs ≥90% EPIC ≥90% Side of Injury

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10 62 11 276

70 Yes Yes

Contralateral Contralateral Ipsilateral Ipsilateral Contralateral Ipsilateral Ipsilateral Contralateral Ipsilateral Ipsilateral Ipsilateral

28 Yes Yes 250 Yes No 78 Yes No 252 Yes No 27 Yes No 60 Yes No 114 Yes No 108 No No No No No No

Abbreviations: ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; EPIC, estimated preinjury capacity; LSI, limb symmetry index.

to sport, a drastic decline from demands faced during preinjury levels of sports ac- tivities. Reduced physical activity levels may result in compensatory adaptations by a subgroup of patients with ACL injury, including decreased muscle strength in the uninvolved leg after ACL injury.11,16,20 De- creased function and performance of the uninvolved limb over time will produce inflated LSIs and may misrepresent the functional ability of the ACL-injured limb.

Eight of 11 patients who suffered a sec- ond ACL injury passed 90% LSI return- to-sport criteria for quadriceps strength and single-leg hop tests 6 months after ACLR. However, 6 of the 8 (4 ipsilateral, 2 contralateral) who met return-to-sport

criteria did not meet 90% EPIC levels in all measures. It is possible that athletes who attained 90% LSIs but not 90% EPIC levels 6 months after ACLR had re- maining bilateral functional deficits that were unresolved after return-to-sport ac- tivities were resumed. Persistent bilateral functional impairments could be a factor in the incidence of both ipsilateral and contralateral second ACL injuries in our cohort, and in the significantly increased risk of both ipsilateral and contralateral second ACL injuries that has previously been reported early after athletes return to sport.17 The small sample of patients in our study with a second ACL injury likely resulted in the large sensitivity and speci-

ficity CIs. Further study is needed with a larger cohort of patients with a second ACL injury to validate the current prelimi- nary findings.

Few studies have examined alternative measurements to LSIs to compare the function and performance of the involved limb after ACLR. Prospective preseason functional testing of athletes is the ideal criterion to provide patient-specific re- habilitation milestones after injury. Pre- injury functional data would eliminate the limitation of EPIC measurements, which require preoperative testing of the uninvolved limb. However, preinjury test- ing requires extensive resources and time commitments, making widespread imple- mentation in high school, college, and rec- reational settings unrealistic. The benefit of including preoperative rehabilitation in postoperative outcomes after ACL in- jury is clear,7 and this period presents an opportunity for objective measurement of baseline uninvolved-limb function to later compare the involved limb during return-to-sport testing. Age-, sex-, and sports-matched normative values present an alternative strategy to patient-specific preinjury data and EPIC measurements, but are not widely developed.5,14

The high number of patients who passed return-to-sport criteria but failed to meet preoperative levels of knee func- tion in the uninvolved limb raises con- cerns regarding current return-to-sport practice guidelines. Despite evidence that stringent objective return-to-sport crite- ria minimize the risk of additional knee injury,8 the requirement for only 80% to 85% symmetry or absence of any objec- tive criteria is frequent.3 The cutoff of 90% symmetry within this study as part of the University of Delaware return-to- sport criteria represents one of the most demanding criteria published and cur- rently used in ACL return-to-sport test- ing.1,3 However, even when meeting these strict criteria, symmetry measures under- estimated the baseline functional perfor- mance of many patients.

The current findings provide grounds for discussion regarding the validity of limb

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 47 | number 5 | may 2017 | 337

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on August 6, 2021. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2017 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

symmetry and current return-to-sport cri- teria after ACL injury. The nature of the current analysis limits our ability to develop strong conclusions about the superiority of EPIC measures over LSIs in decreasing risk of second ACL injuries, because EPIC lev- els were not computed during the 6-month functional testing. Thus, further bilateral strengthening and neuromuscular train- ing to achieve 90% EPIC levels were not implemented. Other limitations include a small sample size, the low occurrence of second ACL injuries, and cohort attrition (including patients tested on different dy- namometers). However, the current study does highlight the need for rigorous test- ing of objective return-to-sport criteria to establish best practice for safe clearance to return to sport and to improve rates of second ACL injury. Determination of the most valid and reasonable reference against which to compare the function of the involved limb must be included.

CONCLUSION

Even with the use of rigorous return-to-sport criteria, recovery of knee function is frequently over-

estimated when using measures of limb symmetry. Preliminary evidence suggests that the inability to restore knee function exhibited prior to ACLR may increase risk for second ACL injuries. The current findings raise concern about whether the variable return-to-sport criteria utilized in current clinical practice after ACL injury are stringent enough to achite